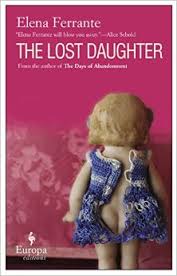

The short novel I finished last night is called La figlia oscura (The Lost Daughter). On the surface it is a simple narrative: a 40-some Italian intellectual rents a beach apartment for a month one summer. Her ex-husband and two grown daughters live in Toronto. Most days she takes her books and notebooks to the beach and swims, sunbathes, prepares her courses for the next academic year, and watches people, especially an extended family of nouveaux-riches from Naples: they fascinate and repel her; they resemble the people she grew up with, people she couldn't wait to get away from. She is particularly drawn to a young mother who reminds her both of herself, and of her daughters. Their lives will briefly intersect.

Under this simple narrative is a storm of emotions that replay the crises in the narrator's life--her abandonment of her children for three years when she was starting her career as a writer and couldn't develop a sense of herself as a person apart from her family. Her turbulent relationship with her own mother. Social class. Her sexual life.

What is remarkable about this story is not how it is told (a straightforward linear narrative of some weeks in the life of the narrator, broken up by dense returns to the past, full of emotional turbulence and extended, probing analysis of her feelings and the roots of her feelings). What is remarkable is the depth and honesty of the feelings and the intellectual powers brought to bear on what might appear to be small events, but which are, in fact, wars she is still fighting.

And alongside this raw, brutal analysis, an erotics of place, of things, of food. The book teems with life of all kinds--disgust but above all gusto. Energy. Range. The scenes at the beach, in the pine wood on the way back to the apartment, at a dance, at the market, in the kitchen.

Is it because I am a woman--and god knows we are hard on one another--that I want to find reasons why this should be a woman's book, rather than a universal book? The more I think about these books, and writing about them helps me sort out my thoughts, the more I think they are outstanding, in any terms. Not genteel tidy little poems, big messy canvases. I can hardly imagine how much energy and persistence it must have taken to write them. A lot of stuff must have got broken in the process.