There are a variety on campus, not quite one per building, but close. The quality of the espresso counts, but also the clientele. There's one in the main quad near the English department I like, especially in the citrus season because it is in the middle of a citrus orchard: grapefruits, oranges, kumquats. Business School not so good, I mean, the coffee is good, but the customers tend not to be my sort of folks. My preference is for the one outside the main library that satisfies all my criteria. I can sit there for a good long while with my finger in a book and an empty cup, listening to the buzz of conversation around me.

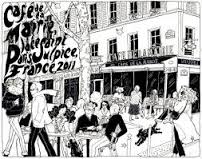

In Paris, the café I am most often tempted by is the Café de la Mairie, on the Place St Sulpice. It is old, run down, grubby, venerable. The waiters are all pre-war. Georges Perec wrote a book about it. It has a quiet upstairs if quiet is what you want and a bustling downstairs and, weather-permitting, a terrace, covered, heated in winter. I like the seats inside the front window. Some sad day someone will buy out the owners, whoever they are, (as happened with the Hotel Récamier across the Place), and turn it into a glossy tourist attraction on the order of Les Deux Magots, but for now, it's authentic.